Guardians of the Homeland: Militarizing Values in 'High-Risk' Neighborhoods in Tegucigalpa

/

Carmen's 6-year old daughter just started classes in a public elementary school in the Henry Merriam neighborhood in Tegucigalpa, Honduras. The majority of the students and teachers that attend the school live in the adjacent neighborhood Flor del Campo and walk the short distance to school every day.

When arriving to school this year, Carmen was given a one-page letter requesting permission for her daughter to participate in a program for three months called Guardianas de la Patria or Guardians of the Homeland, held every Saturday from 7 am to 3 pm for children between six and nine years old at the First Infantry Battalion. She was told that the purpose of the program is to "teach children values" but not given any more details about the scope of the program.

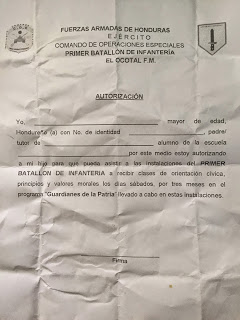

Photo caption: The letter that Carmen was given at her daughter's school about the Guardians of the Homeland program

When describing the general reaction of other parents and the kids in the school, Carmen told me that parents seemed enthusiastic to enroll their children in the program, noting that its an opportunity for children to play outside - something that is limited in the Flor del Campo since communal spaces have been privatized - as well as act as a daycare for parents that work on Saturdays. She told me that the kids of the school all seemed to want to attend including her daughter who kept insisting she wanted to participate.

Roughly a week later and after the program had started, Carmen told me that approximately 30 children that attended the first day, did not want to return the following Saturday. To encourage their parents to keep sending them, parents were invited to attend the following week to see what the program is all about.

Carmen refuses to allow her child to participate. She has heard that the program has been widely criticized by various Honduran human rights organizations including the Committee of the Relatives of the Detained and Disappeared (COFADEH) and Casa Alianza. According to Casa Alianza, "the militarization of children and youth is not the best way to foster and promote human, civil, and moral values to educate citizens of our country." Some see the program as drawing children in 'high risk' neighborhoods into the armed forces and teaching them respect for the military - something that the military has not earned given their well-documented involvement in corruption, organized crime, and human rights violations.

The selection of the school where Carmen's daughter is studying for the Guardians of the Homeland program seems strategic rather than coincidental. Given that Flor del Campo is currently the site of a Military Police base that was built inside the grounds of a recently privatized community soccer field, the program may go hand-in-hand with the government's militarization strategy in the neighborhood. It is also a key location for various programs that claim to help reduce violence and insecurity and stop gang activity in this high risk neighborhood, most of which are coordinated with and through local National Party representatives. These programs include Pintando mi Barrio, Recreovias, Centros de Alcance, funded by the Juan Orlando Hernandez government, the U.S. Embassy, USAID, and Honduran groups including the evangelical organization Alliance for a More Just Society (ASJ).

Photo caption: A young child carrying an imitation rifle as he marches with his classmates in the Independence Day celebration parade in Tegucigalpa, September 15, 2014.

When arriving to school this year, Carmen was given a one-page letter requesting permission for her daughter to participate in a program for three months called Guardianas de la Patria or Guardians of the Homeland, held every Saturday from 7 am to 3 pm for children between six and nine years old at the First Infantry Battalion. She was told that the purpose of the program is to "teach children values" but not given any more details about the scope of the program.

Photo caption: The letter that Carmen was given at her daughter's school about the Guardians of the Homeland program

When describing the general reaction of other parents and the kids in the school, Carmen told me that parents seemed enthusiastic to enroll their children in the program, noting that its an opportunity for children to play outside - something that is limited in the Flor del Campo since communal spaces have been privatized - as well as act as a daycare for parents that work on Saturdays. She told me that the kids of the school all seemed to want to attend including her daughter who kept insisting she wanted to participate.

Roughly a week later and after the program had started, Carmen told me that approximately 30 children that attended the first day, did not want to return the following Saturday. To encourage their parents to keep sending them, parents were invited to attend the following week to see what the program is all about.

Carmen refuses to allow her child to participate. She has heard that the program has been widely criticized by various Honduran human rights organizations including the Committee of the Relatives of the Detained and Disappeared (COFADEH) and Casa Alianza. According to Casa Alianza, "the militarization of children and youth is not the best way to foster and promote human, civil, and moral values to educate citizens of our country." Some see the program as drawing children in 'high risk' neighborhoods into the armed forces and teaching them respect for the military - something that the military has not earned given their well-documented involvement in corruption, organized crime, and human rights violations.

The selection of the school where Carmen's daughter is studying for the Guardians of the Homeland program seems strategic rather than coincidental. Given that Flor del Campo is currently the site of a Military Police base that was built inside the grounds of a recently privatized community soccer field, the program may go hand-in-hand with the government's militarization strategy in the neighborhood. It is also a key location for various programs that claim to help reduce violence and insecurity and stop gang activity in this high risk neighborhood, most of which are coordinated with and through local National Party representatives. These programs include Pintando mi Barrio, Recreovias, Centros de Alcance, funded by the Juan Orlando Hernandez government, the U.S. Embassy, USAID, and Honduran groups including the evangelical organization Alliance for a More Just Society (ASJ).

Photo caption: A young child carrying an imitation rifle as he marches with his classmates in the Independence Day celebration parade in Tegucigalpa, September 15, 2014.